The President, the Envoy and the Talib: 3 Lives Shaped by War and Study Abroad

03.03.2019

Source: The New York Times

By Mujib Mashal

Feb. 16, 2019

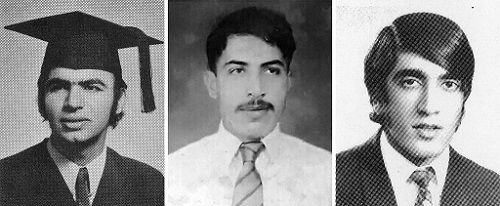

From left, Ashraf Ghani, now president of Afghanistan; Sher Mohammed Abas Stanekzai, now the chief Taliban negotiator; and Zalmay Khalilzad, the Americans’ peace envoy.

KABUL, Afghanistan — Today, they are representatives of three central parties to the Afghan war, caught up by a frenzied effort to find an endgame to decades of violence.

But during the last stretch of peace their generation has known, in the 1970s, the three young Afghans — Ashraf Ghani, Zalmay Khalilzad and Sher Mohammed — were all busy finding themselves while studying on scholarships abroad.

During those years, Mr. Ghani and Mr. Khalilzad, now the Afghan president and the chief American peace envoy, were completing degrees in Lebanon at the American University in Beirut, a vibrant hub of ideologies and intellects during a turbulent time in the Middle East. They enjoyed the Mediterranean beaches, went to dances and met their future wives.

The third Afghan, now known as Sher Mohammed Abas Stanekzai, the chief negotiator for the Taliban, spent those years in military fatigues at the foothills of the Himalayas, training at India’s most prestigious military schools. On breaks, his batch of young Afghans would find themselves in the hills of Kashmir, or on the sets of Bollywood films hoping for a photo with the stars.

Each of their lives captures an arc of the long Afghan conflict. And their differing paths and personalities are now converging at center stage of a desperate geopolitical drama.

Mr. Ghani, Mr. Stanekzai and Mr. Khalilzad now. As young men Mr. Ghani and Mr. Khalilzad studied in Beirut and earned doctorates at American universities. Mr. Stanekzai trained at prestigious Indian military schools.

To end a war that has lasted, in one way or another, for 40 years is no easy task. And though Mr. Ghani, 69, and Mr. Khalilzad, 67, have a remarkable amount of shared history, they have increasingly been at odds over how to approach the Taliban.

The two first met as teenagers, 53 years ago, on an exchange program in the United States, Mr. Ghani recently said.

After both men finished degrees at the American University in Beirut, Afghanistan’s descent into war in the late 1970s put them in the United States again. Mr. Khalilzad earned his doctorate at the University of Chicago, and Mr. Ghani earned his master’s and doctoral degrees at Columbia University, where Mr. Khalilzad started working as an assistant professor.

But even in their student days, the two had notably different styles.

During college in Beirut, Mr. Ghani was more socialist-leaning, and Mr. Khalilzad more capitalist. In his speeches, Mr. Ghani has hailed Mohammad Daoud, who dethroned his own cousin the king in 1973 to declare Afghanistan a republic and himself its president.

In one of his books, Mr. Khalilzad made a point of recalling Mr. Daoud unfavorably. The first time he encountered the future president, he wrote, was when he saw Mr. Daoud leave his vehicle on a highway to beat up a driver who wasn’t getting out of the way and then bite off the man’s left ear.

“They have two very different personalities,” said Akram Fazel, who overlapped with Mr. Ghani and Mr. Khalilzad at American University in Beirut. “Dr. Ghani was working more on self-reliance. He was very focused on his books, and he kept to himself. Dr. Khalilzad was more about consensus and participatory ways — and for him life wasn’t just studies, it was about enjoyment, too.”

Those who have known the two men say part of the current chill in the relationship stems from a fundamental clash in how they operate, as well. By nature, Mr. Ghani is firm in his own ideas, while Mr. Khalilzad is more about patching together a compromise from what is in front of him.

Today, Mr. Ghani and his aides are frustrated by what they see as their American partners’ rushing into a deal that could ensure them an exit but that could unravel a fragile Afghan state.

Mr. Ghani’s advisers worry that Mr. Khalilzad is cooking up an endgame with the Taliban that is skirting around the Afghan government.

As evidence, they cite one of Mr. Khalilzad’s first meetings with the Afghan president after becoming the American envoy: Mr. Khalilzad had already met with the Taliban, but for some reason denied having done so when Mr. Ghani asked him about it, the aides say.

The relationship has remained cold since. Mr. Ghani has struggled to rally a consensus for his plan for peace, built around the insistence that his government lead any negotiations with the Taliban. The insurgents still won’t accept the idea.

Mr. Khalilzad, on the other hand, makes the rounds in Kabul, meeting all the power brokers he has known from his decades of involvement with the Afghan portfolio. His ease with the opposition makes Mr. Ghani’s aides even more suspicious that Mr. Ghani is being cut out.

“This is not about Zal and Ashraf,” Mr. Ghani said to Mr. Khalilzad in one of their first meetings, referring to him with a shortened version of his first name that friends use. “This is now about the United States and Afghanistan.”

The turns in the life of the Taliban negotiator, Mr. Stanekzai, are even more remarkable.

When Mr. Stanekzai, who is thought to be in his early 60s, was training at Indian military schools, back home ideological lines were already firming up. On one side, a communist approach looking toward the Soviet Union; on the other, a wave of Muslim Brotherhood conservatism.

Some of Mr. Stanekzai’s former classmates in India say he largely shied away from politics. But they recall that he leaned toward personal conservatism, including avoiding nonhalal meat.

“He was the most disciplined of his batch, very focused and organized,” recalled Abdul Razique Samadi, who, as Mr. Stanekzai’s senior at the Indian Army cadet college, had oversight over him. “Even if he smoked a cigarette, he would do it away from our attention.”

After the Soviets invaded Afghanistan in 1979 to support the communist government in Kabul, Mr. Stanekzai and some of his classmates became more political. Instead of returning to Kabul, he went to Pakistan to join the anti-Soviet resistance. He had two skills that came handy in a guerrilla movement that relied on foreign intelligence agencies for supplies: English proficiency and military prowess.

Mr. Stanekzai became a top aide to one of the main guerrilla commanders, Abdul Rab Rasoul Sayyaf. His role was as a liaison with Pakistani military intelligence — a relationship that, according to those who have known him, has shaped his political career since. (It has perhaps also been a bitter pill for India to see a man who trained at elite Indian military schools become an asset of its enemy’s intelligence service.)

While ideologically Mr. Stanekzai was with the anti-Soviet mujahedeen, as an urbanite he didn’t quite fit socially, one friend who knew him well in the 1980s said. In Quetta, Pakistan, where their group operated, he would often go out to restaurants with his wife, a subject of gossip among the fighters. The friend recalled Mr. Stanekzai’s berating his fellow mujahedeen for outdated notions about keeping women hidden at home.

When the Pakistan-backed Taliban took over Kabul, sweeping in after the anarchic civil war that followed the Soviet withdrawal, Mr. Stanekzai became deputy foreign minister. His English skills again made him a focal point for the international news media and diplomats, a voice for a government that banned public roles for women.

He traveled to the United States to seek, unsuccessfully, diplomatic recognition by the Clinton administration. His name regularly appeared in the Taliban newspaper, Shariat.

In 1998, Shariat recorded a change in Mr. Stanekzai’s fortunes: He was replaced as deputy foreign minister, and then stopped appearing in news reports altogether for a long stretch.

According to several officials in Kabul at the time, Mr. Stanekzai ran afoul of the Taliban leadership, possibly for reasons involving abuse of power and a lax attitude toward alcohol.

Mr. Stanekzai was put under house arrest, and was said to have been a personal focus of anger by the Taliban leader Mullah Muhammad Omar at the time, the officials said.

What saved Mr. Stanekzai, according to his friends, was his continued connections with the Pakistani military intelligence agency, which wielded leverage over the Taliban leadership. A few months later, he reappeared in a demoted capacity, as the deputy minister of health.

Mr. Stanekzai, in a message sent from his office, denied the allegations of misconduct and said his move from the foreign ministry to the health ministry was routine government reshuffling.

Today, Mr. Stanekzai serves as the insurgency’s chief envoy, directly negotiating with the Americans and leading delegations to places like Moscow and Beijing.

His is the face across the table from Mr. Khalilzad’s during recent negotiations. But it remains unclear — and central — whether he will ever sit across from Mr. Ghani, that other former scholarship student shaped by war and time abroad.

------------------------------------------------------

Source: The New York Times

Link: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/02/16/world/asia/afghanistan-ghani-khalilzad-stanekzai.html

Share This

Your comments on this