The Ghosts of Afghanistan’s Past

18.04.2013

ON March 10, Afghanistan’s president, Hamid Karzai, shocked Western leaders by declaring that recent attacks proved that the Taliban “are at the service of America.” The implication was clear: terrorists were colluding with the United States to sow chaos before America’s planned withdrawal in 2014. American and European leaders, mindful of the blood and treasure they’ve expended to defend Mr. Karzai’s government, were baffled and offended.

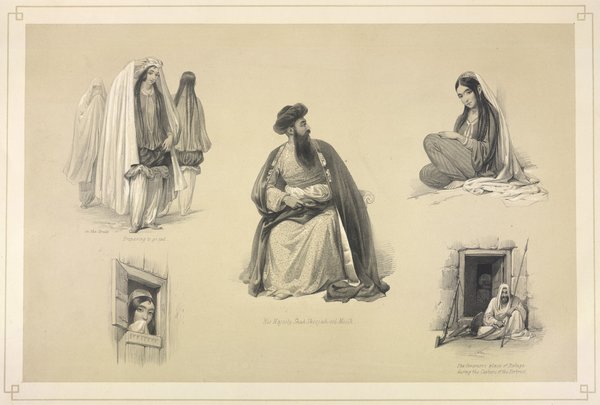

Shah Shuja ul-Mulk and other drawings, published in “Sketches in Afghaunistan” (1842) by James Atkinson.

But to students of Afghan history, Mr. Karzai’s motivation for publicly spurning foreign powers was quite obvious. A Taliban news release on March 18, which received little notice in the Western press, declared: “Everyone knows how Karzai was brought to Kabul and how he was seated on the defenseless throne of Shah Shuja,” referring to the exiled Afghan ruler restored to the throne by the British in 1839. “So it is not astonishing that the American soldiers are making fun of him and slapping him on the face because it is the philosophy of invaders that they scorn their stooge at the end ... and in this way punish him for his slavery!”

The Taliban inadvertently put their finger on a key factor in understanding Mr. Karzai’s psychology. After all, as an elder of the Popalzai tribe, Mr. Karzai is the direct tribal descendant of Shah Shuja ul-Mulk, Britain’s handpicked ruler during the first Western attempt at regime change in Afghanistan in the mid-19th century.

And although few in the West are aware of it, as the United States prepares to withdraw from Afghanistan, history is repeating itself. We may have forgotten the details of the colonial history that did so much to mold Afghans’ hatred of foreign rule, but the Afghans have not.

Today, Shah Shuja is widely reviled in Afghanistan as a puppet of the West. The man who defeated the British in 1842, Wazir Akbar Khan, and his father, Dost Mohammed, are widely regarded as national heroes. Mr. Karzai has lived with that knowledge all his life, making him a difficult ally — always keen to stress the differences between himself and his backers, making him appear to be continually biting the hand that feeds him.

In 2001, top Taliban officials asked their young fighters, “Do you want to be remembered as a son of Shah Shuja or as a son of Dost Mohammed?” As he rose to power, the Taliban leader Mullah Omar deliberately modeled himself on Dost Mohammed, and, as he did, removed the Holy Cloak of the Prophet Muhammad from its shrine in Kandahar and wrapped himself in it to declare jihad, a deliberate historical re-enactment, the resonance of which all Afghans immediately understood.

The parallels between the current war and that of the 1840s are striking. The same tribal rivalries exist and the same battles are being fought in the same places under the guise of new flags, new ideologies and new political puppeteers. The same cities are being garrisoned by foreign troops speaking the same languages, and they are being attacked from the same hills and high passes.

Not only was Shah Shuja from the same Popalzai sub-tribe as Mr. Karzai, his principal opponents were Ghilzais, who today make up the bulk of the Taliban’s foot soldiers. Mullah Omar is a Ghilzai, as was Mohammad Shah Khan, the resistance fighter who supervised the slaughter of the British Army in 1841.

The same moral issues that are chewed over in editorial columns today were discussed in the correspondence of British officials during the First Afghan War. Should foreign troops try to “promote the interests of humanity” and champion social reform by banning traditions like the stoning of adulterous women? Should they try to reform blasphemy laws and introduce Western political ideas? Or should they just concentrate on ruling the country without rocking the boat?

As the great British spymaster Sir Claude Wade warned on the eve of the 1839 invasion, “There is nothing more to be dreaded or guarded against, I think, than the overweening confidence with which we are too often accustomed to regard the excellence of our own institutions, and the anxiety that we display to introduce them in new and untried soils.” In this early critique of democracy promotion, he concluded, “Such interference will always lead to acrimonious disputes, if not to a violent reaction.”

Just as Britain’s inability to cope with the Afghan uprising of 1841-2 stemmed from leadership failures and the breakdown of ties between the British envoy and Shah Shuja, the strained and uneasy relationship of NATO leaders with Mr. Karzai has been a crucial factor in America’s failures in the latest imbroglio.

Afghanistan is so poor that the occupation can’t be financed through natural resource wealth or taxation. Today, America is spending more than a $100 billion a year in Afghanistan: it costs more to keep Marine battalions in two districts of Helmand than America is providing to the entire nation of Egypt in military and development assistance. And then, as now, the decision to withdraw troops has turned on factors with little relevance to Afghanistan, namely the state of the occupier’s troubled economy and the vagaries of politics back home.

History never repeats itself exactly, and there are some important differences between what is taking place in Afghanistan today and what took place during the 1840s. There is no unifying figure at the center of the resistance, recognized by all Afghans as a symbol of legitimacy and justice: Mullah Omar is no Dost Mohammed or Wazir Akbar Khan, and the tribes have not united behind a single leader as they did in the 1840s.

Moreover, the goals of the conservative, defensive tribal uprising that brought colonial rule to an end were very different from those of today’s Taliban, who wish to reimpose an imported Wahhabi ideology on Afghanistan’s diverse religious cultures. And most important, Mr. Karzai has tried to establish a broad-based, democratic government, which, for all its many flaws and prodigious corruption, is still much more representative and popular than the regime of Shah Shuja ever was.

Mr. Karzai is keen to learn the lessons of his forebears’ failures. When my book came out in India in January, he got hold of a copy and read it. “Our so-called current allies behave to us just as the British did to Shah Shuja,” he told me. “They have squandered the opportunity given to them by the Afghan people.”

Mr. Karzai believes that Shah Shuja didn’t stress his independence enough, and he made clear that in his own last year in office he is going to act in such a way that he will never be remembered as anyone’s puppet.

William Dalrymple is the author, most recently, of “Return of a King: The Battle for Afghanistan, 1839-42.”

Source: New York Times

Link: http://www.nytimes.com/2013/04/14/opinion/sunday/why-karzai-bites-the-hand-that-feeds-him.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0

Share This

Your comments on this

| Akhouri Sinha | 04.08.2013 - 08:04 | ||

A well written article, but too late after 12 years of war. This should have been written before the war was authorized by the Congress and President Bush. You could have sent copies of the Great Game that was written in the 18-19th century. This war is essentially a replica of the last one. | |||